Serit arbores quae alteri seculo prosint – “He that plants trees labours for future generations.”

Caecilius Statius, quoted by Cicero. Motto of John Quincy Adams and his family, among others

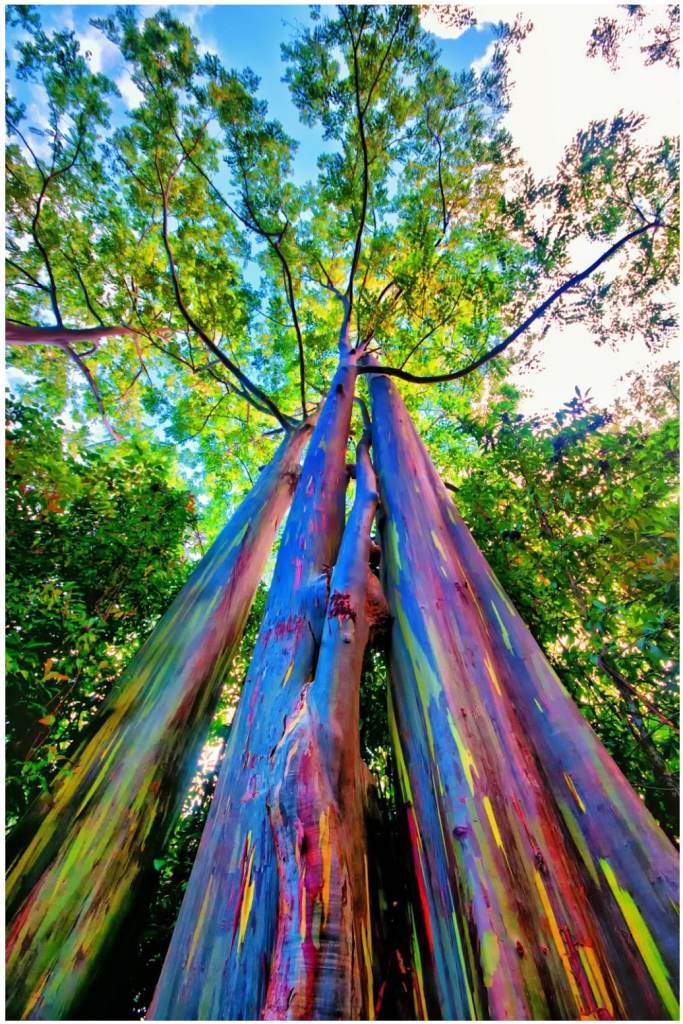

This is a guest post by Dr. Antone Martinho-Truswell regarding a highly unusual tree, his adventures working its wood, and his thoughts about permanence. Enjoy.

What Does It Mean to Build Permanence?

Woodworkers – and especially we odder, curmudgeonly, hand tool woodworkers – have a vexed relationship with permanence.

On the one hand, spend any time reading, listening, or talking to a woodworker of any integrity (not least our distinguished host, Mr. Covington), and you will inevitably hear about building things that last, creating furniture or structures that will outlive the creator. Or else you might hear lamentation of the impermanent, throw-away culture represented by particle board, OSB, melamine, wire nails, and so forth and so on. Stan writes regularly here about building for future generations, about tool chests that preserve and workshop stools that endure. When we chop a mortice or fit a dovetail, the idea is that the end product is permanent – the strength and durability of the outcome justifying the labour-intensive process of creating it

And yet: wood. We are not stonemasons. We are not goldsmiths. We work with a biological material, one subject to biological processes such as mold, rot, borers, gnawing things, weather, sunlight, fire and friction which eat and wear away at wood until it’s gone. Japan’s venerable old wooden structures, record holders across all human construction efforts, pale in age compared to those made of stone. Wood perishes as do all living things (at least since Valinor was sundered from the sphere of the Earth).

This is the story of a permanent wood. A wood as magnificent as it is rare, a wood that is itself a lesson in permanence, and my attempts to make beautiful things for now and the future.

Old and Young Places

I like to think about old things. I was born and grew up in Southern California, where almost everything is new, even the old things. I remember as a child a small water tower near my elementary school, proudly fronted by a sign announcing that it was the oldest building in the area – an august 25 years old. The tower is older now and so am I, but there were old trees around even then. Up north, there are sequoias and redwoods, and of course, the oldest of all, bristlecone pines. I was young then, and didn’t think too much about wood or lumber, but I knew the trees were old.

As a young man, I moved to England for graduate school, and the world was much older. There was a sense of permanence, in the material things at least: old buildings and old furniture and old books and old wood. Oaken chapel pews and blanket chests and linenfold panelling – the sorts of adornments that, in the USA, are the enviable preserve of grand old institutions in grand old East coast cities, but in the UK, found in all manner of great and humble places. But the trees weren’t so old. England’s ‘green and pleasant land’ is green with farms and fens, but not so much old forest anymore. Like much of Europe, over aeons humans have harvested so much timber that little old-growth forest remains, only secondary growth, coppices and managed woodland. The trees in England are fairly young because the culture is relatively old. I was not yet a woodworker, and I did’nt think much on trees and timber at the time, but I knew the culture was old.

As a married man, I moved to Australia, and here I remain. The prevailing culture – that of the settlers rather than the indigenous people of Australia – is young, and so are the trees. Mostly.

Australia’s frequent natural fires mean that most of the trees that grow here are adapted to grow fast and big, but not long. Generations of forest turn over quickly – in ecological terms that is – with bushfires killing off adult trees and causing their scattered seeds to germinate and grow a generation of newer, younger trees. What’s more, as in America, the brash, youthful settler culture did not have a good track record as stewards of the natural gifts of the island continent, and the few old hardwood forests that once existed have been over-exploited.

Perhaps with age comes wisdom, but now I am both a father and a woodworker, and I ponder permanence, and wood, a great deal, and what all this youthful forest means for woodworking here in the sunburnt country.

Hard, Stringy Wood

If you know anything about Australian woods, you know they have a well-deserved reputation for being really, really hard.

The vast majority of our forests and the trees that grow in them are the various and many species of eucalyptus and its near relatives, with two qualities that make them a mixed blessing to woodworkers.

First, they are fast growing, so as to quickly repopulate the land after fire, and second, they are extremely hard – the softest commercially available eucalyptus wood is called “Victorian Ash” (or “Tasmanian Oak” – same wood, different source) in the timber trade with a hardness similar to white oak or rock maple. The hardness of other varieties can easily range up into ipe and ebony territory.

The result is an abundance of eucalyptus wood great for things like flooring and fenceposts, but fast growth makes it especially stringy, which together with phenomenal hardness makes it difficult to work with handtools. That same Victorian ash, the most common of all hardwoods in commercial use here, is among the best behaved, and a straight grained piece can take a nice glassy finish from a hand-plane, but we have nothing commonly available with the smooth texture of a maple or beech. Victorian ash works like oak at best. The other good furniture eucalypt is Jarrah, which is a lovely orange-brown colour and less splintery than most, but it’s expensive and a good bit harder than maple, so still a challenge. Moreover, it comes from Western Australia, which, along with Victoria, banned all native forestry at the start of 2024, so it is likely to recede to only niche use in the future.

There are many other beautiful, softer, easier working, and often fragrant Australian hardwoods, but for one reason or another all of them are scarce and hard to track down.

There are few species under plantation production here, and the fast-growing eucalypts crowd out most other species in our forests, so the best cabinetry timbers, like acacias and mahogany relatives, are rare. If you find these timbers for sale, it’s usually from a small-time operation that harvested a fallen tree – so you have to wait around for luck to smile on you. I try to snap up Australian Rosewood priced reasonably. The vast tracts of cabinet timber we once had – the famed Australian Red Cedar, which is actually a mahogany cousin, for example – were all irresponsibly exploited down to commercial extinction decades ago. A permanent culture of wood use requires a forestry industry with an eye toward permanence, which we didn’t have for a long time, and many argue we still don’t – hence the aforementioned bans and the limited selection of commercial wood.

A few government agencies and private companies are trying to improve sustainable forestry in Australia focusing on Australian blackwood (Acacia melanoxylon). This species should not be confused with the African blackwood of oboe, clarinet and bagpipe fame. Australian blackwood is a dead ringer for Hawaiian koa, and is its closest living relative. It has a rich, deep, brown colour with the same gleaming chatoyancy of koa, but its name comes not from the colour of the seasoned wood, but rather the black color the sap turns sawyers’ hands.

It’s a breathtaking timber deserving of widespread admiration, and one of the few beautiful cabinet timbers down here that weren’t over-exploited to near extinction in the last century. The blackwood timber industry is apparently a bit wiser than their forebears, and so harvests less and charges more to promote sustainability. It’s the nicest timber that can be bought here straightforwardly, and is priced accordingly.

The Ships that Took Our Trees

Of particular interest to users of Japanese tools and Japanese woodworking methods and mindsets are softwoods, and this is where Australia is confusing. There are no true pines native to any part of the Southern Hemisphere – but settlers insisted on naming all the fascinating and unusual softwoods down here “pines” – and then importing a northern hemisphere species for most of our plantation wood.

Norfolk Island Pine

When Britain established the first penal colony at Sydney in 1787, the site was chosen partly because it was thought to offer a good strategic back-up to the British claims on Norfolk Island – a speck 900 miles out into the Pacific. The trees covering this island – Norfolk Island pines – were thought to be particularly valuable to the Royal Navy, as they tended to produce ramrod-straight single trunks, almost as if replacement masts had been conjured up from the Earth. However, the timber proved too flexible for masts, and the idea was abandoned, though the Norfolk pines got their second act as a popular ornamental plant (including a few all the way back in my home town in California).

Hoop Pine

Much more useful is hoop pine, a near cousin of the norfolk pine that grows on the Australian mainland, and is our only plantation-grown native conifer. I’ve made shoji from hoop pine; it has nice straight grain producing a good shine when hand-planed. The only other commercially available native softwood is Australian white cypress which has a beautiful smell and is famously insect resistant, but unlike most softwoods it’s harder than American oaks. It also doesn’t grow very big, so is mostly used for knotty, sapwood-sapwood edged fence posts, or equally knotty floorboards and decking. I understand that it is not a sustainably managed species, and conservationists often recommend against its use.

Monterey Pine

The Australian construction industry relies on plantation grown monterey pine (also called radiata or pinus radiata) for all of its general purpose lumber. This is an import from California, now very rare in its natural habitat but grown all over the Southern Hemisphere to compensate for a dearth of native pine species. It is a particular pet-hate of Australian woodworkers, in online forums and general conversation, who lament its often crumbly texture and poor strength. I don’t hate it though – it can take a lovely plane finish and the wide grain does make for beautiful patterns on clear, flat sawn boards.

Huon Pine

Like all Australian trees, huon pine is misnamed. It isn’t a pine at all but rather the only member of its genus – more akin to a cypress than anything else, yet still not a cypress, a thing of its own.

Fans of Tolkien’s works may lament that its name is Huon and not Huorn, but no tree was ever more deserving of association with Tolkien’s tree-herding Ents, that ancient race of sentient defenders of the forest.

Huon pines grow only in Tasmania, and only in the wet and mountainous western regions protected from fires. Provided they have that protection, they may achieve something most Australian trees do not – great age. Huon pines grow incredibly slowly, barely thickening as century after century wash over them, living at least 2000-3000 years, with some thought to be even older. This is best evidenced in the astonishing tightness of their annual growth rings. It is not uncommon to see specimens with annual growth less than half a millimetre – or to put it another way, the trees gain less than two inches of trunk radius per century. While immensely slow, these trees can still grow immensely large when given that precious critical thing – time. They are probably the longest-lived trees in the Southern hemisphere, and certainly in Australia.

There are lots of small huon pines growing now, though few big ones. They should be huge, but they are not, because the great ones were all mostly cut down to build boats – a vast fleet of huon pine watercraft were constructed in Tasmania, using up most of the big trees. The promise of the perfect tree for shipbuilding that had fallen flat on Norfolk Island paid off big time in Tasmania with the huon pine. The reason for the single-minded use of these ancient trees for shipbuilding will become obvious, but as a result of this hasty zeal, they are now the single most protected species of tree in Australia, both to allow the forest, with Ent-like patience, to recover, and to preserve the few very old and very large specimens that remain.

Beyond the Grey Rain-curtain

These trees are old, though their lives are but the beginning, and death, as Gandalf once taught young Peregrin Took before a fateful battle, is just another path beyond which the journey does not end. This is, cynically, true of all wood that gets put to human purpose, but it is true in a special way for huon pines because of a unique chemical in their wood. Not unlike other fragrant cypress-like softwoods – including Japanese hinoki – huon pines contain great amounts of oil, in this case, an oil called methyl eugenol that protects them from insects and other wood-hungry nasties. Methyl eugenol is, as it happens, the ticket to eternity for wood.

For whatever reason, methyl eugenol, in the very high concentrations in which it is found in huon pine, is astonishingly successful at preserving timber. Huon pine timber is highly prized for shipbuilding because it’s easy to bend and work, completely impervious to insects and fungus, and readily survives the rigors of the aquatic environment. All that ever seems to happen to huon pine is that the surface turns grey in the sun – much like teak. And then it simply endures.

And I mean it endures. The 3,000-year age of living huon pines is one thing, but researchers have found fallen huon pine logs on the floor of the forest that have lain there, unmolested by decay, for as much as 38,000 years! Not petrified, not fossilized, just oily wood under a weathered surface, simply enduring.

These characteristics are also why we still have a bit of precious huon pine timber available nowadays, reclaimed from time to time from old boats and old furniture, as durable and enduring as ever. Moreover, the foresight that was missing when the trees were mostly cut down a century ago was not blind when hydroelectric dams came to Tasmania. In the 1970s, with two valleys set to be flooded, the Tasmanian government allowed loggers to go into the valleys and cut down the pines – but not to take them. The loggers, working in tall boots even as the dam waters were rising, would leave the logs where they fell, to float up to the surface of the new lake as the waters rose.

That was 50 years ago – the logs are still there, floating on the lake. The outer layer turns grey to about 1-2mm in, and then, inside, the creamy golden wood, as perfect as the day it was felled, endures. The decades afloat harms it not at all, and every year a tiny portion is licensed to be taken for restoration and preservation jobs.

This is all the unreclaimed huon pine that there is or ever will be for woodworkers to use, and they estimate they have about 50 years’ worth left at current extraction rates. But with the wood so impervious and eternal, what is already in cabinets and drawers and tables and ships will continue to circulate and be reused. It is a wood with true permanence.

An Unexpected Responsibility

At this point I will enter the story to share the most harrowing and rewarding of my experiences as a woodworker.

By chance, I had the opportunity to acquire three large slabs of huon pine, cut and dried in ages past but never used. Compared to the tiny crafting boards and turning blanks that are generally available (at great price), this was a bit of a windfall. I could have, with all cynicism, listed each one for sale for several hundred dollars, pocketed the profits, and went on to buy more quotidian woods. I did not do this for two reasons.

First, and perhaps most pointedly, with visions of epoxy pours and hairpin legs plaguing my dreams, I was overcome with a sense of responsibility to “protect” this precious wood – whatever that means. I wish to acknowledge, in self-reflection and humility, that I am an amateur woodworker. A reasonably experienced and meticulous one – but an amateur nonetheless, albeit one who works with hand tools and has the hand tool mindset. My work is fine but not perfect. But I suppose I like to think that the tool marks I leave here and there, occasional tear-out, and other mistakes that remain have a certain honesty and worthiness to them, becoming of a slab of great age. Vanity of vanities, all is vanity…

More than that though, I saw in these slabs of huon pine, and in the legends of these trees, an opportunity for permanence. Here were three great hulking slabs of a tree older than the nation-state it was felled in (I counted 800 growth rings on one of the slabs – and it wasn’t even a centre slab), thick and strong, and made of the closest wood comes to being an imperishable material. Here was the opportunity, if it was ever going to exist, for a piece of furniture that might outlive the memory of my name.

It had to be a table. Only a table could use to best effect the wide expanses of precious wood – laying them out on full display for all who saw them to admire. No matter how perfectly I might make a cabinet or chest, it would not do justice to the material. And, as history, archaeology, and literature show, only a table is so intimately connected to life and family and holiness by its proximity to hungry mouths, little hands, and eager minds as they first do their colouring and then their maths homework, and then their college applications. Only a table is ever so truly loved by generations as to be worthy of wood older than all those generations combined. I simply couldn’t bear cutting the beautiful slabs into small pieces. So for months I fretted; and worried; and stressed about the crushing responsibility of making the first cuts.

The Weight of History

I am an apartment woodworker. My family home is a house in the mountains west of Sydney, but I work as Dean of a university college and we live most of the time in the Dean’s residence, an apartment on campus. I am blessed with a very patient and indulgent wife and an apartment that happens to have a sort of wide corridor I use as a tiny woodshop. Space is still limited, though, and I try not to stockpile wood (in the interest of stockpiling tools – ahem). So, three slabs, two metres long and the best part of a metre wide, mocked me each time I had to shuffle past them. And still, I fretted.

I eventually decided upon a refectory table so that no matter how many chairs are crammed around it, none clash with the legs. And with a strong stretcher tusk-tenoned into each leg to allow it to knock down, so that I could make it big but still fit it through doorways. Most importantly, I needed to keep the two 800mm wide boards that made the tabletop flat – so sliding dovetails across the bottom to counteract any cupping. And those sliding dovetails would be a perfect place to pin the top to the legs, with removable dowels, again so it could be knocked down to move. Drawbored mortise and tenon joints to hold the I-shaped legs together without glue (since all that wonderful oil makes gluing troublesome anyway). A kanna-shiage (handplane finished) top for beauty and touch, with just a light coat of oil and hard wax, so that the wood itself can be appreciated. A magnificent vision. Complex and well-chosen joinery. Perfection worthy of the tree. Entirely beyond my experience or skills…

I had to start by getting to know the wood. Before any cutting or marking or anything, I realized I could not confront the massive task I had set myself without first knowing what it was to get huon pine under saw and plane, to see, feel it, and smell it.

.

I hoisted one of the slabs onto my sawhorses, and with a few strokes of the little aogami roughing plane on the left, and a few more of the shirogami finishing plane on the right, I had my first look at the slab, and my first curls of huon pine shavings. (No, Stan, I don’t London finish my plane bodies. They are dirty, it’s patina.)

The smell – oh the smell. The smell of huon pine is unlike anything I have ever experienced. It is sweet and rich and almost creamy, but without even a hint of sugariness or caramel, nor any of the medicinal notes of cedars or cypress. I suppose the aroma is a little like gardenia flowers, but different. And it’s persistent. I saved bags of little offcuts that are no less fragrant now than a year ago.

The scent was such that I almost did not notice the figure at first. From some angles, nothing more than a very tightly grained, golden softwood, with rippling grain caused by the irregular growth of the tree’s surface over the centuries is visible. But when the light strikes the surface of the top at the right angle, a shimmering sea of lamellar rays cutting across the grain pop out, almost obscuring the grain with its gleam. Beautiful but subtle – much like the scent. This image and this aroma is now linked with permanence in my senses.

With the feel, smell and appearance of the wood now embedded in my mind I began to feel more confident about beginning my table project. One serious concern remained, however, namely: tear-out.

Layout That Fills the Workshop

I started in with trepidation, hoisting the two closest matched slabs onto my horses and getting to work. In my little shop, I have no room for a great big assembly table, so the slab was my workbench, and took up the whole shop. Here you can see my cramped little shop, replete with little atedai against the wall, assorted tat taped and hung on the walls (including my Palm Sunday palm, awaiting the coming Ash Wednesday), my tool chest brusquely stolen from Stan’s design, and a lovely old tansu filled with bric-a-brac.

Layout was painstaking, although not because the joinery was especially complex. Before shaping, the two “I” shaped legs were six simple boards and the stretcher would resemble nothing so much as a 2×4. The only complexity to the initial layout arose from the graceful radius I had planned for the long edges of the two top slabs. I could have cut them with straight edges and cut the curved edges later but that problem would have been unnecessarily wasteful.

One simply cannot waste this wood. If you have any respect or regard for the trees that support our craft, it repulses the conscience to even put plane shavings into shop bins. Moreover, I absolutely refused to cut these slabs in anything but the most efficient, offcut-preserving way. As a result, layout took days (or, rather, nights. Amateur, remember?).

The two surfaces of the slabs I used for the top each had unique flaws and virtues. In the end, curving the tabletop’s edges to accommodate the natural edges and features of the slabs proved effective in maximizing the tabletop’s size while minimizing waste of this rare and valuable wood. For example, in the photo above you can see where the near right corner of the slab narrows towards the end, an inconsistency my layout had to accommodate. This layout was also necessary because two of the slabs were contiguous in the bole and one was not, such that the two contiguous, matched slabs had to be used for the top even though one was somewhat larger than the other.

Dealing with the constraints that imposed this layout taught me important lessons in collaborating and compromising with the wood. In line with Japanese tradition, I knew I wanted the “outside” surface of the board to be oriented upwards in the table, and so my layout prioritized that side. As a result, both slabs ended up with prominent natural flaws on the underside – like greyed areas, bark incursions, and even one gash that looked as though the tree had been struck with a red hot poker.

There is a school of thought in modern, machine assisted, YouTube recorded woodworking that cannot tolerate such defects, no matter how small or natural, in any piece of furniture, demanding they be either removed entirely or filled with colored epoxy. The first approach I reject because wood is natural and I believe it should feel natural. I enjoy the fragrance of the wood, and the feel of running my hand along the underside of the table, sensing the evidence of the tree’s story, together with the tool marks I intentionally left. The latter approach I reject because epoxy is plastic, and I work with wood. The table bears the scars it earned in life, but only reveals them to those with enough appreciation and humility to get down on their hands and knees to gaze upon them.

Putting Blade to Wood

I do not now, and suspect I never will, own a table saw. Someday I might own a bandsaw, but I’m not convinced. In any case, I won’t have any of these things in the house whilst my daughters are young, as much to spare my family’s lungs from dust as to avoid injuries, however unlikely.

So that meant I had to figure out a way to accurately break down these slabs along my layout lines with hand saws, in a room that barely contained the slabs.

I couldn’t do it on the sawhorses – that would require me to stand on the slabs to make the long rip cuts, which seemed risky to their integrity without a supporting table underneath, especially when sawing the narrower pieces. And the slabs were too long and too heavy to comfortably use the Japanese low horse and foot-clamp method, which I am normally fond of for long rips.

The solution I selected was to support the slabs horizontally on one long edge using my 6-inch thick planing beam, with the other long edge supported on low horses with extra boards taped to them to make up the difference in height. This provided enough vertical clearance under the slab for a kataba saw. This arrangement had other advantages too. As I ripped from one end of the slab to the other, I could stand on the slab directly above the supporting planing beam, which was in turn resting on the floor, preventing the slab from shifting position while avoiding downward deflection of the ever-narrowing slabs.

My back did not love this hunched sawing position, but it was more comfortable than you might expect, and in two long sessions of rip-sawing, I had everything broken down to pieces: two wide top planks, each tapered on one edge, two vertical leg pieces, four feet and aprons for the I-shaped legs, and one long stretcher. As it happened (and as you can see below) the offcut from the third slab was almost a perfect extra stretcher. I still have it and will use it for something someday. It is the world’s most magnificent (and I suspect valuable) pine 2×4. The two venerable katabas, one rip and one crosscut, may be seen taking a well-deserved rest after rendering magnificent service.

With designing, planning, layout and rough cutting done the project shifted to the shaping and joining phase requiring greater attention, so I put down the camera, and did not pick it up again until the job was done. Sadly, I don’t have photos of gorgeous shavings rippling off planes, or of the massive Anaya-nomi I used to cut the mortises for the stretcher to pass through the legs, or of the nakin-kanna rounding off edges.

This work was more-or-less conventional furniture-making; taking the neatly rectangular pieces of wood I made in the rip-fest above and shaping them into components using good steel and keen eye. I didn’t follow a borrowed or historic pattern for any of this, but worked out my own take on the refectory style of dining table with two I-shaped legs and a single stretcher.

I made a pattern of a single asymmetric curve using a bit of sturdy brown paper shopping bag, leaving the carry handle attached to hang it on my shop wall throughout the process so it was always to hand. I used this same curved pattern throughout to define all the curves in the project, starting with the concave slope from the mortise in the feet to their toes, the tapers from centre to ends on the vertical legs, and again as the most important curve in the project – the gentle swell of the tabletop’s long edges from one end to the middle and then tapering back to the opposite end again.

Once the base was completed, the conventional woodworking ended and the real gauntlet began – the top.

The top was made with the two long, wide boards shown with my kataba saws in the photo above. At almost 400mm wide each, they were a challenge to handle, a bigger challenge to plane, and an even bigger challenge to keep flat.

The work of planing the wood went alright. The swirly grain of huon pine is not terribly prone to tearout, and like all quality softwoods, is a joy to plane in the direction to which it agrees, producing shimmery, breathtaking surfaces. The trouble is that each 400mm board contained 800 years of growth rings with grain direction changing within each board many times due to storms, cool summers, and a lightning strike or two as empires rose and fell. And with such tight grain an entire century of growth, along with the changes in the tree’s environment that impacted that growth, ended up recorded within a mere five centimetres of width – narrower than the thickness of a standard 70mm kanna – and often without apparent visual clues. As a result, seemingly neat, fine ribbons of shavings pulled end to end would be followed by tiny but significant tearout here and there across the board.

Reader, this took days – days of sharpening by very best white #1, fine mouthed, perfectly (amateur-perfect, mind you) tuned kanna. Days of shaving just exactly to this specific point, in just this direction, just so, to clear up a spot of tear out, then switching sides and going the other way, hoping and praying and watching that I didn’t overstep the boundary and have to start over – which I did, many times. And all the while, awkwardly walking around the massive slab, leaning over it to plane the far side, getting half up onto it like a billiards player, and then doing it all over again on the other slab. There is still some tear out in the surface, especially around the teardrop-shaped bark inclusion that gracefully adorns one corner of the tabletop. But it’s pretty close.

Keeping it Flat

An important aspect of the project was ensuring the wide, solid-wood tabletop remained permanently flat through changes in temperature, humidity, loading and coverings. In the case of such wide slabs, there was only one realistic solution – sliding dovetailed battens on the underside. This design detail had the advantage of providing two level, perpendicular surfaces to connect the legs to the tabletop.

Of course, a hard cross-grain connection between the battens and the tabletop using glue and screws would end in tears after just a few years, so I cut two blind sliding dovetail slots in each half of the tabletop beginning at centre joint of the toward to about 8-10cm of the edges, then cut dovetails into the battens to fit. The two planks hold the battens captive between them once installed, and the friction in the sliding dovetails locks the two slabs together without glue, dowels or hardware.

To use glue anywhere in this project seemed wrong. In any case, the oils in huon pine don’t play nicely with glue, and the joinery connections were the better plan.

I cut the dovetails in the battens and tabletop planks using my cleverest of all Japanese planes – the male and female dovetail plane, a rare beast indeed.

With the battens installed I cut 10cm wide shallow bevels on all four lower edges of the top, tapering the top to create the illusion of a tabletop only 20mm thick from a slab about 40mm thick in the centre. This involved a lot of plane work.

I left the underside a bit more rustic, even allowing large areas of “live” bark to remain as a lagniappe to the worshipful person who surveys the underside. You might think that leaving bark on the underside meant that I contravened the usual practice of Japanese woodworkers of using the outside surface of a plank as the show surface, but no – though not Japanese, I cleave to this principle invariably, but in this case, the history of the tree involved so many twists and turns that the bark inclusion was exposed on the inner surface of the board.

For clarity, allow me to explain what may not be obvious from the photos. The two legs are connected by mortise and tenon joints to horizontal feet at their lower ends and horizontal beams at their upper ends. In turn, the trestle leg beams are connected to the two battens by four dowels, two at each batten, that pass through the beams and battens at an upwards angle. After exiting the batten, the end of each dowel presses tightly against the underside of the tabletop, slightly bending and binding it in place.

To disassemble the table in preparation for relocating it to our home in the mountains outside Sydney, I just need to knock out these four dowels and slide the battens out of their dovetail slots, and knock out the two wedges in the ends of the tusk tenons securing the spreader beam connecting the legs. This design has worked well, and the dowels are strong enough that the table can be lifted and carried by the top alone.

The Finish

Now, a great part of me wanted to leave the wood unfinished, both to enjoy the raw kanna-shiage surface, and to ensure the magnificent smell would not be diminished. But, to provide some protection and give a bit of extra visibility to the lovely grain, I gave the wood a couple of coats of thinned pure natural tung oil, and then rubbed on and buffed out several coats of carnauba wax creating a surface hard enough to help protect the relatively soft wood from dings and scratches. Also, my wife liked the colour better oiled than unfinished, a very important consideration for all of my woodworking efforts.

And that was the job done, and here it is, in its home on the covered veranda of my house:

As you can see, the finish turned the feet, which I cut from a discontiguous slab, a darker color than the rest of the table, but it’s an effect I rather like. The clouded figure of the top shimmers beautifully in the morning light from the East, and the little imperfections quietly witness to handwork, something for me to fret over in my quietude at meals around the table. The horizontal beams at the top of each leg that mate with the battens, not visible in the photos, are identical to the feet, except of course inverted.

I do not think I am testing the permanent nature of this table by using it outdoors – though I may move it inside for a different practical reason: it is now the largest table we have, and has already made a couple of trips inside for big family gatherings. Rather, faced with a true forever wood that can endure against the elements, it seems only right that it should experience them and demonstrate its aplomb. I am glad in the end that I did not glue the centre joint of the top surface because it allows the two slabs to move and stretch a bit on humid days without cracking or busting the seam, and while this does mean they become un-flush for a day or two, they settle back in becoming flush once again when the weather dries out. The table can breathe.

I will inevitably make little corrections as the table and I get used to each other. I remain unsatisfied with the very rectangular shape of the stretcher, and when the time comes to break down and refinish the table I will add some curvature to the stretcher. I will also probably resurface the top perhaps once a decade, as it ages and my skill with a kanna (hopefully) improves. Part of the joy of using a wood that should outlive my bloodline to make a table of great permanence that can be disassembled and reassembled as needed is the anticipation of ongoing minor improvements, and the relationship I and future generations will have with it.

In the end, I still do not quite deserve this wood, because no one does. It is right and just that the Tasmanian government has banned the felling of any more of these trees, and it is right and just that the remaining wood is hard to come by and cherished. I am happy for the opportunity to make something permanent with this magnificently permanent and beautiful material.

Antone Martinho-Truswell is a professional zoologist and amateur woodworker. His work can be found on Instagram at @stjosephwoodworks, where he posts his projects, experiments, and failures, and takes the odd commission. If you enjoy his writing and want to learn more about his day job, his book, The Parrot in the Mirror, is available from booksellers online and worldwide.

To learn more about and to peruse our tools, please click the “Pricelist” link here or at the top of the page. To ask questions, please the “Contact Us” form located immediately below. You won’t be ignored.

Please share your insights and comments with everyone in the form located further below labeled “Leave a Reply.” We aren’t evil Google, fascist facebook, treacherous X, Harvard University, or H. Clinton’s IT dude and so won’t sell, share, or profitably “misplace” your information. If I lie may someone bukkiri my neck.

Leave a comment