Sharpening a crosscut saw. Sharpening a crosscut saw

Sharpening a crosscut saw

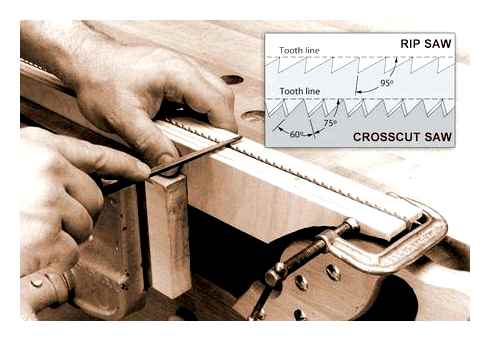

Another View of Filing Angles

Jointing: When jointing the tops of the teeth, a saw jointer makes this easier. However, you could also use one of the jigs in the recommended books below. Engler’s and Lie-Nielson’s books show this best.

Setting:. When setting the teeth, a saw set is critical for this.

If buying one, get one with a pistol-grip, and which accommodates 4-16 TPI. The saw set I use is a Stanley model 42W. It works much better than the models 42 or 432. I have not tried the Stanley model 42X, nor have I tried any of those newer ones available on eBay, so I cannot speak to their abilities.

Increase Set for saws with coarse teeth. Decrease Set for saws with finer teeth.

For very fine saws, the burr from the filing will probably give adequate set.

Filing:. When filing the teeth, hold the blade next to a straight edge (e.g., a 2×4) to ensure consistent gullet depth.

A clamp-on filing guide for the fleam makes this easier. Or use one of the jigs in the recommended books below. Engler’s and Lie-Nielson’s books show this best.

For the triangular file, use the specified size based on the saw’s teeth per inch (TPI) as shown in the lower picture to the right.

Lower Rake angles make the saw’s cutting more aggressive (and faster).

With Fleam at 10°, a crosscut saw acts more like a modified rip saw. At 45°, it requires more resharpening and is less tolerant of variable grain alignment.

Blackburn Tools’ web page, Saw Tooth Geometry, has good visuals to explain Drop (which they call, Slope), Fleam, and Rake.

Information

Videos Presentations

- Getting Started with Western Saws (Vimeo video). This video from Lee Valley is a great overview of various saw types.

- How to Sharpen Your Saws (YouTube video). Mike Updegraff with “Mortise Tenon Magazine” walks through the sharpening of hand saws. It is easy to get lost in the specialized terminology, but Mike gives a dead simple explanation that will be hard to forget.

Website Authors Note: All the posts, pages and tutorials on this website are my original work, there are no spun or rewritten articles. Please feel free to view and comment on any of the posts. Click through to the shared links as well, these were all hand picked by the author with relevance to the script. Disclosure: This post may contain affiliate links, which means that I get a commission if you decide to make a purchase through my links, at no cost to you. Read my disclaimer for more info.

How To Sharpen Your Hand Saw!

Basic Saw Sharpening – Sharpening a saw blade can be done by hand, but it takes a few special tools and some experience to do it right. You only get experience through trying however doing it wrong can ruin the blade. But a dull saw can ruin your work.

Below I will try and give some guidance on sharpening saw blades, however if you feel uncomfortable doing it send your blades in to a professional for sharpening. I am also not covering repairing teeth or cutting new teeth only the sharpening of the teeth on your existing saw blade.

There are many more experienced people out there and many, many write ups on this subject.

Here is a link to one site:

I am a qualified fitter machinist so personally this is not all that difficult but I have extensive training and experience in the use of the tools required for the sharpening process.

As with most processes if you understand it and practice the art of doing it, it will become second nature. At the worst you may learn something that you didn’t know.

I will only cover the sharpening process, information on setting or tuning your saw will not be covered.

There are many good reference sites for the sharpening process and a comparison between them would not go amiss, there may be somethings done by others that would better suit your own needs than my take on the subject.

You will need a saw clamp or vice, this will hold the blade tightly to minimise vibration when sharpening the teeth. Clamps are available to purchase however if you are wanting to do this yourself you can manufacture your own clamp to suit your specific saw or make one base unit and have a few jaw pieces which you can change for different lengths of saw blades.

The clamps or vices that are available for purchase are either cast iron or wood, you will need to decide which is best for you. Disston and Wentworth both have saw vices, I have heard good reports about both makes, if possible avoid ‘no name’ brands.

Personally I have never owned or bought a saw vice, my dad taught me to make one many years ago and I still use the same one, with a few modifications over the years.

I will try and give you a quick guide to making your own vice in a later post. Although there are many ideas and plans out there which could be used if you have the time to search around.

Basic Saw Sharpening

You will need a vice or clamp to sharpen your saw blades, having one is not optional as it is really impossible to sharpen a blade without one.

Place your saw, teeth facing upwards, in your clamp, ensure the section you intend sharpening is held firmly between the jaws of the clamp.

The longer your clamps jaws are, the more difficult it will be to ensure that the blade is held firmly, try and keep this to a maximum of 350mm to 400mm.

You will have to move the blade as you progress down the length of the saw. My clamp is hand made and the clamp jaws are around 350mm and I find this to be perfect for me.

Slow and Steady

The most important thing to remember, this is not a race, go slowly, once you get the hang of it you will speed up naturally however this is a slow process in any case and accuracy is more important than speed.

This can also be very frustrating at times, sometimes no matter what you do it seems to go wrong, the best idea when this happens is to give yourself a time out, leave it for a while and come back later. It will not seem as frustrating when you return.

Remember slow and a light touch will normally always do the trick.

The smaller the saw teeth are the more frustrating it can be, however patience and persistence will pay off, a sharp saw will bring a smile to your face.

Here is another link to an interesting site that has more information:

Files

I use 3 different files, cheap files do not last, spend a little extra and you will have files that will last a long time. If you are a hobbyist or a DIY carpenter you will only buy these files once, they will last for many, many saw sharpening’s. All the files mentioned are triangular in shape for obvious reasons.

Files Types

Tapered files: Our local hardware stores carry most of the Pferd range and I have found these to be great files for saw sharpening.

Blunt saw files: These files are not in fact blunt as the name may infer, they are, unlike tapered files, the same dimensions along the length of the file.

Needle files: Needles files are great to use for finer toothed saws, 11tpi or finer, care must be taken to not go to deep into the gullet of the blade as this could create a to collect sawdust.

The smaller the file the easier it is to control, files longer than 150mm to 180mm, become cumbersome and the file itself becomes larger to create the stability. A good rule of thumb for the file size is, at least half the depth of the file should be greater than the teeth being sharpened. You must find the file and size that suits you.

Age Of The Saw

If your saw is fairly new then the blade was most likely originally sharpened by a machine, or if you have a very old saw perhaps by a professional carpenter with many years experience.

If your saw is old and the uniformity has gone from the teeth and the original sharpening angle cannot be determined then this simple explanation will not be of much use to you.

A note about sharpening saw teeth your stance at the vice can make a big difference in how you apply pressure to the file and you must move as you progress down the saw, this will make a difference as to how the saw is being sharpened. You should stop after a few teeth and adjust your stance to the way in which you began. You should always be able to see what you are doing. Counting strokes I find helps to ensure that you use the same number of strokes on every tooth. Also always lift the file on the back stroke, this will enhance the life of the file.

It will help if you darken the teeth on the blade this will enable you to see which teeth you have already sharpened and which teeth you have not yet filed. I use a dark red marking ink which cleans off easily with a bit of benzine but stays on the blade while I am working on it.

Rip and Cross cut saws

A rip saws teeth are chisel shaped and this allows the saw to ‘rip’ through the wood whereas a cross cut saws teeth are more like knives that cut through the wood.

When sharpening rip saws I file across every second tooth from one side following the existing angle, then turn the saw around and do the exact same from the other side. I always file standing adjacent to the saw, I have seen people doing the same from the front end or the back end, you must do what is comfortable for you however don’t do all the teeth at the same time, you will confuse your strokes and leave the saw more dull than when you started. Always file the teeth at 90 degrees to the blade.

Normally on one or two light strokes are required, use the set of the saw to assist you, always keep the tooth that is bent away from you on your one side so when you rotate the saw it will remain the same. If you have used something to mark the saw this will also assist you to know which teeth you have already completed.

Repeat this process for your crosscut saws as it is much the same the main differences are the first being the angle that the teeth were originally cut at must be maintained, the angle of the rake should not be changed if possible, but if it is changed must not exceed 12 degrees.

Secondly, the fleam angle, the fleam angle is the angle that you file the teeth at, which would typically be 20 to 25 degrees off the perpendicular, where with the rip saw the file is perpendicular. As before file every second tooth, then rotate and file the balance of the teeth, use the same method of marking the teeth to keep track of where you are.

Be aware of your movements, small steady movements will give better results. If you are struggling file only a stroke or two on each tooth, you don’t want to remove too much material, rotate the blade do the same from the other side and repeat the process a few times. It is better to remove too little material than too much.

Another important thing to note is how you file the teeth, this is determined by the set of the teeth. I always start on a side so that the tooth bent away from me is to my left and file towards the handle. – Note I am left handed – so for normal people……try with the tooth bent away from you on your right and file towards the toe.

That is about it, I am not going to cover setting the teeth or any other saw sharpening as I have minimal experience with them. I am sure if you are looking for specific information on these topics there are professionals out there that could assist.

Click on the link below for more information on saw sharpening:

I trust that this was of some use to you and that you can feel the difference when cutting with a freshly sharpened saw.

Follow this link for a simple saw sharpening clamp

Understanding Saw Tooth Geometry

My recent saw sharpening video where I demonstrated the Veritas Saw File Holder has generated a lot of emails with questions about saw tooth geometry. I take this as a good sign that lots of people are actually thinking about sharpening their own saws. Not only that but the introduction of filing guides like the Veritas and the Rakemaker II by Blackburn Toolworks (a great site to check our for more info on this subject) have people thinking in detail about what tooth geometry is best for their work. These little guides open up a level of filing accuracy only previously attempted by saw filing experts. Of course with this comes questions about how this saw tooth geometry actually works. What degree of rake and fleam are best for me?

This is a tough question to answer. Like any sharpening related topic there are many, many opinions and solid justification for each of those opinions. Usually any sharpening discussion is to be entered at your own risk and histrionics should be expected with much wailing and beating of the breast. So here is my sidestepping disclaimer: the numbers I detail below are but one option within the mellifluous multiverse of saw tooth geometry. I give ranges of numbers knowing full well that there are too many variables at play to state one degree of rake and/or fleam is better than another. From body mechanics and stature, to type of wood and degree of seasoning. Don’t forget the phase of the moon and astrological sign either! These are my humble opinions won through hours of sawing with a fair dose of standing on the backs of giants like Herman, Harrell, Wenzloff, and Smith.

Elements of Saw Tooth Geometry

This is a great PDF provided by Tools for Working Wood, go download it!

Pitch, Rake, Fleam, and Set are the elements we should consider. I think that really only rake, fleam, and set are the primary elements and pitch a secondary element. Pitch, the number of points per inch or PPI, plays a role in determining how deep your gullets are and therefore how efficiently the saw carries saw dust away from the kerf. This in turn relates to the speed and the cleanliness of the cut but not nearly as much as the rake and fleam can effect these outcomes. As such I think we can set pitch aside for this discussion since it will be rare that we are actually changing this pitch unless you are making a saw from scratch or restoring a really really beat up and well used saw.

Rake determines the aggressiveness of your cut. This is the angle of the cutting face of the tooth. At 0 degrees, the tooth is vertical and cut very aggressively. One can actually lean the tooth forward to create a positive rake and a very aggressive cut, but also one that is hard to push and start while leaving the undercut tooth a bit weaker. You will find a positive rake on some Japanese saws but the pulling motion and much harder steel adds in some variables that ameliorate the negative effects of positive rake. The more you relax the rake, or increase the angle the tooth slants away from the cut the easier the saw is to push. The teeth can now skate over the wood more easily. This makes starting the cut easier but also it slows down the cut as the teeth have a tendency to lift up and away from the cut. A low rake angle cuts fast but can feel grabbier and also make take more experience to handle. Changing this angle will help you adjust to harder and softer wood as well.

Fleam is the angle across the face of the tooth or perpendicular to the tooth line. By adding fleam you turn the teeth into little knives that slice the grain instead of chop it like a chisel. The more fleam the cleaner the cut you get but the weaker you make the teeth. As the fleam angle increases you get a smaller tooth front and the steel becomes brittle. As such high fleam saws should be used in softer woods that won’t push back so much on the more fragile teeth. The converse to this is a saw tooth with little to no fleam will leave a rougher cut and require more effort to move through the wood. The slicing action that is inherent with fleam is what makes a well tuned crosscut saw do its job without splintering and tearing across the grain.

Set is the amount of offset the teeth have to either side of the tooth line. When we set the teeth we are bending them away from the saw plate to widen the kerf and allow the saw to run without binding. Like the other elements this is a good thing but too much goes wrong very fast. The wider the kerf the more wood you remove and therefore the more work required to push the saw. Likewise the wider the kerf the sloppier the action as the saw plate can now wiggle about in the wider kerf and throw off a precise cut. This is why joinery saws always have less set than rough work hand saws. Also why softer and/or wetter woods need more set because the spongy and sticky saw dust won’t clear as readily from the kerf and more room is needed for the saw to run. If the kerf gets tight not only will the saw bind, but it can deflect in the kerf as it tries to find a way around the build up dust, thus making your saw not run true.

None of these elements should be considering singly. They all relate to one another and should be considered as a whole to create the best tooth geometry for the task at hand. This is very useful as you can compensate, augment, or offset the positive and negative effects of one element by tweaking another.

For example,

If I want my saw to cut fast I will reduce the rake. If I want it to start easily yet still cut fast I will increase the fleam a bit to make the teeth slice more (like skewing a hand plane). This also have the happy effect of making a smoother cut surface. I can also reduce the set to create a cleaner cut since a more uniform tooth line won’t present as jagged an edge to the wood. This allows me to reduce the fleam to make a stronger tooth. The beauty is that by altering all 3 of these in concert can produce the perfect experience. Each one plays a role and tooth geometry should rely on all 3 to do the job.

So what does this mean to you? What degrees should I use for my saws? What follows are some general numbers to use as a guide. Now that you know what changing these numbers will do you can tweak them one way or another to create a saw that performs well in a specific situation or over a wider range of applications.

Set

This is not as cut and dried to the point where I can put a numerical range on it. The reality is that set is measured in thousandths of an inch and most of us don’t have the capacity to even measure this. Professional saw filers have much more accurate setting techniques and a heck of a lot of muscle memory to aid them. For the average woodworker with a pistol grip saw set, it comes down to feel. Most set has a pitch guideline on them that you can adjust to match the saw. The finer the pitch, the smaller the set. My recommendation is to set this adjustment to a pitch that is finer than the actual pitch of the saw you are working on. Sometimes several times finer in fact. set can be added and set can be removed but I find it easier to add more than take it away. Often times the setting process is helpful in adjusting a saw that isn’t running true too so the best thing is to skew to the finer set and then make several test cuts altering the set to get the right feel. With each test cut make sure you saw enough to let friction heat up the saw plate causing it to expand. You may think you have it right only to find the saw plate expands in the middle of a cut and starts to bind.

I find that once I have a saw set, I don’t need to reset it until I have sharpened the saw at least once more. In other words, every 3rd sharpening is a good rule of thumb. So while set is a little more touchy feely than rake and fleam, remember that it is also part of the geometry that effect how the saw cuts. Don neglect to alter the set in order to tune a saw. I have certainly been guilty of just relying on rake and fleam to solve all my problems. Though if I’m being honest usually the adjustments I make in set entail reducing the amount rather than increasing it.

Hopefully this treatise will help you wrap your head around these concepts. Don’t over analyze it but rather relish in our ability to be able to finely tune our hand saws. For the average hobbyist, pitch a number in the middle of the above ranges and you will do just fine. If you are more adventurous and looking for that “perfect” saw, consider each and every task as an equation to be solved with a little creative tooth geometry. Is it any wonder why masters of the saw like Ron Herman have so many saws? Once you solve one of these geometry equations you will find yourself getting more saws and tuning them to specific tasks. Careful this is a slippery slope and soon you will be talking about witchcraft like sloping gullets and progressive rake and fleam.

What To Know About Sharpening a Handsaw

megaflopp/Getty Images

Thinking of learning how to sharpen a handsaw? As an experienced woodworker, it’s a skill I personally find largely unnecessary. Here’s why.

Our editors and experts handpick every product we feature. We may earn a commission from your purchases.

Though electric woodworking tools are better designed and more readily available than ever, handsaws still have their place in every workshop. If you’re an aspiring or seasoned woodworker, you most likely own at least one. If so, you’ve probably wondered if it’s worth learning how to sharpen a handsaw. The short answer is, probably not.

A Case Against Sharpening a Handsaw

A few highly skilled master woodworkers still sharpen their handsaws, but they’re rare. I don’t know a single serious woodworker besides myself who’s ever attempted it.

This doesn’t mean it’s never worth doing. But for most beginner and intermediate woodworkers, it’s probably a waste of time, and here’s why.

Hard-point handsaws don’t need sharpening

Many modern saws never need sharpening. You simply replace them when they get dull. The design and construction of modern handsaw teeth make this possible.

The teeth come from the factory razor-sharp. And they’re made of hardened steel, too tough to be ground down by files used to hone traditional handsaws. This toughness means the teeth maintain their edge for a long time. Woodworkers call these tools “hard-point saws.”

Not all modern hard-point saws cut well. One that has been consistently great for me for more than a decade is this handsaw from Irwin. It crosscuts extremely fast and accurately. It can even handle rip cutting in a pinch.

Sharpening handsaws requires specialized skills and tools

A good portion of woodworking skill involves keeping cutting tools sharp. Proper sharpening takes lots of time, skill, practice and often special equipment. That’s why it makes sense to minimize the amount of sharpening you have to do.

For tools like chisels, gouges and planes, sharpening is unavoidable. But for handsaws, hard-point models make sharpening unnecessary.

In the past, before hard-point saws were invented, many woodworkers sent their saws away to be sharpened by a specialist who had all the specifically shaped guides and files needed to sharpen each saw tooth. Those brave few who attempted it themselves were usually in for lots of boring, finicky work.

Hand-sharpened saws don’t stay sharp for long

Even if you invest all the necessary time and money to learn how to sharpen a handsaw and do a perfect job, the saw won’t stay sharp for long.

Crosscut and Ripcut What is the Difference

Like all woodworking cutting tools, the steel of sharpenable handsaws is soft enough to be ground. That means these saws can never stay sharp as long as hard-point saws. I’ve personally tested a hand-sharpened non-hard-point handsaw against my hard-point Irwin. I found the Irwin cut about 10 times as much wood before getting dull.

How To Care for a Handsaw

Whether you opt for a modern hard-point handsaw or stick with an older sharpenable style, it’s important to take good care of it. Here’s how:

- Keep it in a safe, dry place to avoid rust.

- Never store it with the teeth near any other metal tools that might dull it.

- Always fit a handsaw blade guard over then teeth before putting it away.

When Should I Sharpen My Handsaw?

Some skilled woodworkers still like to kick it old school and sharpen their non-hard-point saws. There are a few situations when employing this skill still makes sense:

If you’re interested in woodworking without power tools

Having begun my own woodworking career with this impulse, I can certainly understand the desire to challenge yourself as a true woodworking purist and not use electricity at all, except to light your shop.

If this is your goal, hand sharpened rip cutting handsaws will rip cut better than general purpose hard-point saws.

If you don’t have a table saw or circular saw

Most modern woodworkers use a table saw or a hand-held circular saw for rip cutting. Both give faster, better results than handsaws.

The problem is, table saws are big and expensive. Not everyone can afford one, which leaves the smaller, more budget-friendly option of a circular saw.

Unless you clamp a straightedge to your workpiece for every cut, making perfectly straight cuts with a circular saw takes considerable skill. It takes skill with a rip cutting handsaw, too. But because the cut doesn’t happen nearly as fast or aggressively as with a circular saw, beginners are less likely to mess up.

If you like the idea of skipping the table saw and circular saw for rip cutting, learning to sharpen your rip cutting handsaw makes sense.

How To Sharpen a Handsaw

If you’re determined to sharpen your old handsaws by hand, know that saw sharpening techniques vary greatly, depending on:

Restoring and Putting Crosscut Saws To use

- The shape and size of the saw’s teeth.

- How many teeth per inch (TPI) your saw has.

- Whether it’s meant for crosscutting, rip cutting or both.

Fair warning: It’s not easy to do a good job. The first step is purchasing the necessary tools.

Tools for sharpening a handsaw

- Saw set tool: A plier-like tool used to bend each saw tooth outward slightly.

- Set of saw files:These triangular files grind away metal on each saw tooth to make it sharp again.

- Handsaw clamps: These long, thin clamps fit in a benchtop vice and grip the blade of your handsaw as you sharpen it. It’s possible to make your own by rip cutting most of the way through the center of a 1- x 1-in. strip of wood of equal length to your saw, then positioning your saw blade in the cut and clamping the wood strip in your vice.

- Benchtop vice: This holds your saw clamp in place on your bench as you sharpen.

Clamp your handsaw in place

Choose a handsaw clamp of sufficient length to hold the entire blade. Fasten the saw clamp to your work area with a benchtop vice. Place the saw upside down in the saw clamp with the teeth protruding from the top, with not much of the blade itself showing.

Set the saw teeth

Handsaw teeth need to be bent outward at a specific angle to work properly. This ensures the kerf of the blade is slightly wider than the blade itself, and prevents the saw from binding.

With use, saw teeth bend in. That’s why the first step is resetting the teeth with a saw setting tool. Adjust the tool for the number of teeth per inch of your handsaw, then set each tooth individually.

Choose the right file for sharpening your handsaw

Whether you’re sharpening a rip cutting or crosscutting handsaw, you’ll need a saw file with a shape that matches the tooth profile. The side thickness needs to be at least twice as wide as the height of your saw’s teeth to ensure even file wear.

Level each tooth

Pass the file gently over the tips of the teeth once or twice, holding the file perfectly level. This will level each tooth so the newly sharpened points are all in the same plane. The tiny flat spot created by the file on the end of each tooth will be shiny, a good visual reference for not grinding away too much metal.

File each tooth

Beginning with the tooth of your saw nearest the handle, hold your saw file with two hands and perform short, controlled strokes against the blade. If your saw isn’t too dull, it might only take one or two strokes per tooth. If it’s really dull, it might take more.

Sharpen each tooth in sequence, one at a time. Make sure you maintain the same pressure and angle on all file strokes.