A Guide to Hand Saws. Saw tooth setter tool

A Guide to Hand Saws

In this comprehensive guide, we will cover the different types of hand saws and explain how to use a hand saw.

The purpose of this guide is to highlight some of the many different types of hand saw on sale and to identify what each saw is best used for. Our ultimate aim is to help you narrow down your options when considering buying a hand saw for the sorts of jobs you’ll be taking on.

In the sections below, you’ll find guidance on how to use a hand saw alongside an overview of the most popular types of hand saws. We will also cover some basic information about their key characteristics, differences and uses. Popular hand saw types we’ll cover include tools used for cutting wood and plasterboard, tenon saws, pruning saws, and numerous other important varieties of hand saws.

What are Hand Saws?

Hand saws (sometimes written as handsaws) are an essential piece of hardware for any well-stocked toolbox. In fact, they’re right up there with hammers, chisels and spanners in terms of the most commonly used tools for a range of general home improvement and maintenance projects.

While modern power tools offer fantastic speed and convenience in many sawing applications, by no means are they a universal solution. In many scenarios, factors such as accessibility, convenience, weight, safety or finesse can mean that a hand saw is a far better option than a powered tool.

Of course, there are many different types of hand saws available. As with all manual cutting tools, knowing which type of hand saw to use for which task is vital if you want to get the best results.

The Different Types of Hand Saws

As noted above, there are many different types of hand saws available. Some are designed to be used as multi-purpose, general use sawing blades. Others are precision engineered specialist tools for optimal performance in far more specific sawing tasks.

At this point, it’s worth noting that names for the various basic hand saw types aren’t always entirely consistent between different suppliers, manufacturers and users. This can lead to some confusion. For example, some common saw types and naming conventions you could encounter while shopping for a simple timber saw might include:

- Rip saw

- Crosscut saw

- Panel saw

- Short cut saw

- Box saw

- Wood saw

- Tenon saw

- Back saw

- Dovetail saw

- Pruning saw

- Plasterboard saw

- Coping saw

- Fine finish saw

- Fretsaw

- Hacksaw

- Frame saw

- Bow saw

- Hardpoint saw

- Keyhole saw

- Punch saw

- Compass saw

- Pull saw

- Dozuki saw

- Ryoba saw

- Kataba saw

- Pole saw

- Veneer saw

over, you’ll sometimes find several of the common names listed above being used almost interchangeably, often referring to what looks like the same basic hand saw type.

In many cases, the precise differences between these various subtypes can be subtle. Alternatively, even when the saw designs themselves appear to be different, their actual uses might, in fact, be similar.

For example, you may see ‘wood saws’ designed for straightforward timber cutting identified as either rip saws, panel saws or crosscut saws. Tenon saws might be listed as back saws or dovetail saws by some suppliers. Different hand saws all intended for cutting holes, curves and other precise shapes include punch saws, keyhole saws, compass saws, fretsaws, and more. Additionally, some tools may be identified by other characteristics entirely, such as fine finish saws or heavy-duty models.

To keep things simple, in this guide we’ll FOCUS on the four major categories of hand saws by their specific material uses. wood saws, metal saws, plasterboard saws, and pruning saws.

Hand Saw TPI Guide

Hand saw TPI. teeth per inch. is a really important consideration when choosing the best type of manual cutting tool for a specific job or material. In fact, TPI is often one of the biggest differences between the many different hand saw types on offer.

To give a very simple overview of TPI, the general rule of thumb is that the more teeth per inch a saw blade has, the finer the cut (and the neater the end result) will tend to be.

As you’d expect, this means that tools designed for fine or detailed work. such as fretsaws or coping saws. will have higher TPI counts. High TPI counts are also generally preferred when working with thinner woods and metals.

Hand saws intended primarily for lower precision tasks. such as pruning branches, cutting planks, or cutting sheet timber panels down to size. will usually have lower TPI ratings. Similarly, low TPI counts tend to be the better option for thicker, green and treated woods.

Hacksaws, used mainly for cutting metal and plastic, can be seen as something of an exception to the above rules. They often have relatively high TPI blades due to the physical demands of those materials, but they are seldom used for detailed work.

In terms of a basic hand saw TPI guide, you’ll usually find products sorted into the following approximate categories:

- Blades with fewer than 7 TPI will generally be sold as coarse-toothed saws

- Blades with between 7-11 TPI will often be classed as medium-toothed saws

- Blades with 12 or more TPI are typically labelled as fine-toothed saws

In the next section, we’ll look at different types of hand saws for use on various specific materials.

Hand Saws for Cutting Wood

It can be tricky to identify the best hand saws for cutting wood, because ‘cutting wood’ can cover such a diverse range of jobs. Sawing through a log or tree branch is a very different task compared to cutting a neat hole in a furniture panel. Making a smooth curve on a piece of hand-crafted woodwork, meanwhile, is completely different once again.

Each of these scenarios requires the user to cut at varying speeds and forces in order to ensure the job is done correctly. Unsurprisingly, this means that there is a different ‘best’ hand saw for each situation. In general, you’ll want to observe the TPI rule of thumb:

- Stick to fine-toothed saws for jobs that demand slower speeds and higher precision. teeth per inch usually imply a finer blade, meaning that your cut will be neater but progress through thicker or harder woods will be gradual

- Coarse-toothed saws are great for cutting through thicker or tougher materials quickly. The wider gaps between teeth mean that they can tear out more wood with each thrust of the blade, but the end result won’t be particularly neat

So-called ‘hardpoint saws’ can be an economical and convenient option for a range of simple woodcutting jobs. These tend to be relatively basic saws with plastic moulded handles and sharp, induction-hardened teeth. While many general-purpose hardpoint saws will get the job done on most types of wood, bear in mind that their treated blades typically can’t be sharpened. Once the teeth on a hardpoint wood saw have dulled, the entire tool must be replaced. This makes them a more suitable option for people who will only use hand saws for wood occasionally.

Hand Saws for Cutting Metal

When choosing a hand saw to cut metal, many people opt for the traditional hacksaw, consisting of a narrow and fairly flexible hacksaw blade tensioned between the two ends of a rigid c-shaped frame. This simple, familiar tool is a widely used and trusted option for cutting thin metal sheets by hand.

Once again, though, it’s worth considering various other facets of the task when choosing the best hand saw configuration for the job. When it comes to choosing hand saws for cutting metal, it’s important to bear the following in mind:

- The specific material properties of the metal type you’ll be cutting

- The size and thickness of the sheet you’re working on

- The shape of cut you need to make

- The neatness of finish you need to achieve

Even if you’ve already decided on using a hacksaw to cut your metal sheet, paying attention to variables such as TPI count and blade material can make a big difference to the difficulty of the job. Much like with wood saws, hand saws for metal are most effective when TPI count and material properties are matched:

- Lower TPI blades are better for coping with tougher or thicker metals such as iron and steel but will create a much rougher cut

- Higher TPI blades will produce a finer cut but are generally preferred for thinner or softer metals like aluminium and copper

An Illustrated Guide to Hand Saws

As we’ve seen above, there are many different types of hand saw sold for a broad and diverse range of jobs. When asking what are the main types of hand saw you’re likely to be choosing from, you may find the slight variations in terminology used by different suppliers can quickly become confusing.

If so, the following picture guide to some common hand saw types should help:

General-purpose hand saw

Similar Name/s :

Hardpoint saw

Similar Name/s :

Plasterboard saw

Similar Name/s :

Tenon saw

Similar Name/s :

Fine finish saw

Similar Name/s :

Hacksaw

Similar Name/s :

Pruning saw

Similar Name/s :

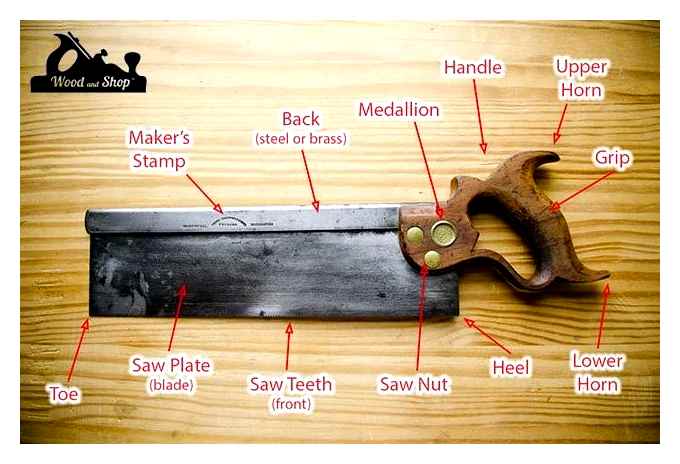

The Anatomy of a Hand Saw

The diagram below should help you get to know the anatomy of a hand saw in greater detail. It will also help you understand the correct terminology for each component of the saw.

What are Tenon Saws?

A tenon saw is a special type of back saw. Any saw with a reinforced spine can be called a back saw, but a tenon saw has specific uses and characteristics for achieving controlled, precision cuts in wood.

What is the Definition of a Tenon Saw?

They’re usually quite easy to spot, thanks to the following identifying features:

- A rigid spine along the top (non-cutting) side of the blade, generally made from steel, brass or (less often) wood

- Tenon saws usually have a fairly short and sturdy blade, ending in an enclosed pistol grip handle designed to protect the user – typically, this can’t be removed

- The most common TPI counts for a tenon saw blade are between 10-14, giving a slower but more controlled cut than coarser hand saws

- Some tenon saws are designed to cut on the forward stroke only (a ‘push saw’, as opposed to a ‘pull saw’), although you should be aware that this isn’t always the case

What are Tenon Saws Used for?

Tenon saws are mostly used for short, accurate cuts in demanding precision jobs such as joinery or furniture-making. Tenon saws get their name from being commonly used in cutting smaller or more intricate pieces of wood, and especially for making joints.

The characteristic back saw spine helps to keep the saw blade from bowing or bending while cutting. It also limits the depth of cut you can make. This is a necessity when cutting mortise and tenon joints, hence the common name for this type of hand saw. Tenon saws are best used for cutting across the wood grain, as opposed to along it. that’s where you’ll need a rip saw or panel saw.

What are Pruning Saws?

As the name suggests, hand pruning saws are intended for quick and easy cutting back of overgrown branches, logs, twigs, and other thick or coarse garden wood and foliage. They tend to feature a medium-long blade, which is often curved, and a fairly low TPI count for more effective sawing of green and live shrubbery. It’s common to see folding pruning saws on offer for easier year-round storage.

Smaller, straight-bladed pruning saws are ideal for cutting thinner diameters of very young, green or sap-heavy wood and branches. These pruning saws tend to feature a slightly higher TPI count, typically around 7-8.

Larger, curved-blade pruning saws with wider tooth spacing (5-7 TPI) are better for thicker, older and harder branches. This more rugged design allows for quicker removal of bush and tree limbs up to about 2.5 inches in diameter. Fewer strokes will be required, but the cut will not be as smooth or delicate.

Plasterboard Saws

Plasterboard saws, often called jab saws or drywall saws, are specifically designed for cutting holes and voids in wall or ceiling panels.

They’re identified by their medium-length, fairly narrow blades that taper to a sharp point. Plasterboard saws often feature a curved handle at the wider end of the blade. Their overall look is quite similar to compass saws and the two have similar properties, except the plasterboard saw blade is generally shorter.

Plasterboard is typically made from a combination of gypsum plaster, paper, and possibly plywood. Drywall saws for cutting plasterboard are ideal for making rough cut-outs around electrical sockets and other fittings or appliances, as their fine-tipped blades make it much easier to punch through and pierce the panel in order to get the cut started.

These saws are seldom used for any kind of precision work as the TPI count tends to be relatively low on a plasterboard saw, leaving a fairly rough finish that will be hidden behind a fascia or finishing panel. The blade is also somewhat flexible, making angled or curved cuts easier. For precision work in drywall, many professionals tend to use a safety knife, also known as a box cutter or Stanley knife.

How to Sharpen a Hand Saw

The question of how to sharpen a hand saw comes up fairly often. Saws that have been heavily used, or improperly stored over long periods of time, can easily end up feeling much duller than they originally did. When this happens, it usually becomes fairly obvious within a few pulls or pushes of the blade across the cutting material.

With a dull hand saw, the blade won’t bite easily at the start of a cut, lines are difficult to keep neat or precise, and making progress through thicker materials can be laborious. By contrast, the best cutting hand saw will be well aligned and will always have sharp teeth.

Sharpening a hand saw isn’t necessarily difficult, but it is important to carry out the task properly and safely. Furthermore, some saws aren’t good candidates for sharpening in the first place. For instance, this is usually the case with hardpoint saws, whose teeth have been treated and aren’t designed for lifelong use.

For some cheaper hand saws, blades (or even entire tools) can be more economical to replace altogether, especially once you factor in the time and other materials needed to perform a proper repair. It’s also worth noting that poor sharpening technique can be just as damaging as neglecting the tool in the first place:

- With rip cut saws, if one or two teeth end up slightly shorter than the others (either through heavy use or imprecise sharpening), the chances are that it won’t completely ruin a hand saw’s action

- If one or two teeth end up longer than the rest, though, you’ll quickly start to notice uncomfortable dragging and juddering when you saw

- For crosscut saws, the ‘set’ of the teeth (their alternating angles towards and away from the midline of the blade) may also need adjusting over time. If the set of the teeth is too narrow, the blade may bind when cutting. However, if the set of the teeth is too wide, it may feel loose in the kerf and show a tendency to wander

With all that said, once you’ve bought a good hand saw, it may very well prove to be something you want to keep in your tool kit for a long time to come. In that case, at some point, you will need to sharpen the teeth. Good saw sharpening technique can help you achieve great results with hand saws over many years of intensive use.

There’s both a simple and a more complex approach to sharpening hand saw teeth. The more complex method (particularly for crosscut saws, as noted above) might involve any of several additional tools, such as a saw tooth setter. Here is a handy outline of the more basic sharpening technique for rip cut saws.

Tools You Will Need:

Both of these files are commonly found in good file sets. Any size triangular file that fits well between the saw teeth will be suitable.

Steps:

- First, set the blade as low down in the vice as you can, while leaving the teeth themselves exposed as this will minimise wobble and flex as you file

- Next, use the flat mill file to level out the teeth. Hold it level across the tops of the teeth, perpendicular to the blade. Use light, even pressure in a side-to-side action along the full length of the blade, creating a small flat top on each tooth. You will be able to see these new flattened tops as bright, shiny areas when held to the light

- Once you have done this, you will need to switch over to the taper saw file. Place the file in the gap between two teeth, angled slightly towards the tip of the saw so it rests against the spine of the tooth being sharpened. Again, make sure to hold it level and perpendicular with the blade. Make two to three light sideways passes in the same direction for every tooth along the full length of the blade, maintaining a consistent action and number of strokes each time

- Once the shiny, flattened top of every tooth has been reduced to a pinpoint, all at a consistent size, the saw has been successfully sharpened. Make sure to test our your newly sharpened hand saw and if necessary, go back and make adjustments in small increments until the issue is resolved

Understanding Saw Tooth Geometry

My recent saw sharpening video where I demonstrated the Veritas Saw File Holder has generated a lot of emails with questions about saw tooth geometry. I take this as a good sign that lots of people are actually thinking about sharpening their own saws. Not only that but the introduction of filing guides like the Veritas and the Rakemaker II by Blackburn Toolworks (a great site to check our for more info on this subject) have people thinking in detail about what tooth geometry is best for their work. These little guides open up a level of filing accuracy only previously attempted by saw filing experts. Of course with this comes questions about how this saw tooth geometry actually works. What degree of rake and fleam are best for me?

This is a tough question to answer. Like any sharpening related topic there are many, many opinions and solid justification for each of those opinions. Usually any sharpening discussion is to be entered at your own risk and histrionics should be expected with much wailing and beating of the breast. So here is my sidestepping disclaimer: the numbers I detail below are but one option within the mellifluous multiverse of saw tooth geometry. I give ranges of numbers knowing full well that there are too many variables at play to state one degree of rake and/or fleam is better than another. From body mechanics and stature, to type of wood and degree of seasoning. Don’t forget the phase of the moon and astrological sign either! These are my humble opinions won through hours of sawing with a fair dose of standing on the backs of giants like Herman, Harrell, Wenzloff, and Smith.

Elements of Saw Tooth Geometry

This is a great PDF provided by Tools for Working Wood, go download it!

Pitch, Rake, Fleam, and Set are the elements we should consider. I think that really only rake, fleam, and set are the primary elements and pitch a secondary element. Pitch, the number of points per inch or PPI, plays a role in determining how deep your gullets are and therefore how efficiently the saw carries saw dust away from the kerf. This in turn relates to the speed and the cleanliness of the cut but not nearly as much as the rake and fleam can effect these outcomes. As such I think we can set pitch aside for this discussion since it will be rare that we are actually changing this pitch unless you are making a saw from scratch or restoring a really really beat up and well used saw.

Rake determines the aggressiveness of your cut. This is the angle of the cutting face of the tooth. At 0 degrees, the tooth is vertical and cut very aggressively. One can actually lean the tooth forward to create a positive rake and a very aggressive cut, but also one that is hard to push and start while leaving the undercut tooth a bit weaker. You will find a positive rake on some Japanese saws but the pulling motion and much harder steel adds in some variables that ameliorate the negative effects of positive rake. The more you relax the rake, or increase the angle the tooth slants away from the cut the easier the saw is to push. The teeth can now skate over the wood more easily. This makes starting the cut easier but also it slows down the cut as the teeth have a tendency to lift up and away from the cut. A low rake angle cuts fast but can feel grabbier and also make take more experience to handle. Changing this angle will help you adjust to harder and softer wood as well.

Fleam is the angle across the face of the tooth or perpendicular to the tooth line. By adding fleam you turn the teeth into little knives that slice the grain instead of chop it like a chisel. The more fleam the cleaner the cut you get but the weaker you make the teeth. As the fleam angle increases you get a smaller tooth front and the steel becomes brittle. As such high fleam saws should be used in softer woods that won’t push back so much on the more fragile teeth. The converse to this is a saw tooth with little to no fleam will leave a rougher cut and require more effort to move through the wood. The slicing action that is inherent with fleam is what makes a well tuned crosscut saw do its job without splintering and tearing across the grain.

Set is the amount of offset the teeth have to either side of the tooth line. When we set the teeth we are bending them away from the saw plate to widen the kerf and allow the saw to run without binding. Like the other elements this is a good thing but too much goes wrong very fast. The wider the kerf the more wood you remove and therefore the more work required to push the saw. Likewise the wider the kerf the sloppier the action as the saw plate can now wiggle about in the wider kerf and throw off a precise cut. This is why joinery saws always have less set than rough work hand saws. Also why softer and/or wetter woods need more set because the spongy and sticky saw dust won’t clear as readily from the kerf and more room is needed for the saw to run. If the kerf gets tight not only will the saw bind, but it can deflect in the kerf as it tries to find a way around the build up dust, thus making your saw not run true.

None of these elements should be considering singly. They all relate to one another and should be considered as a whole to create the best tooth geometry for the task at hand. This is very useful as you can compensate, augment, or offset the positive and negative effects of one element by tweaking another.

For example,

If I want my saw to cut fast I will reduce the rake. If I want it to start easily yet still cut fast I will increase the fleam a bit to make the teeth slice more (like skewing a hand plane). This also have the happy effect of making a smoother cut surface. I can also reduce the set to create a cleaner cut since a more uniform tooth line won’t present as jagged an edge to the wood. This allows me to reduce the fleam to make a stronger tooth. The beauty is that by altering all 3 of these in concert can produce the perfect experience. Each one plays a role and tooth geometry should rely on all 3 to do the job.

So what does this mean to you? What degrees should I use for my saws? What follows are some general numbers to use as a guide. Now that you know what changing these numbers will do you can tweak them one way or another to create a saw that performs well in a specific situation or over a wider range of applications.

Set

This is not as cut and dried to the point where I can put a numerical range on it. The reality is that set is measured in thousandths of an inch and most of us don’t have the capacity to even measure this. Professional saw filers have much more accurate setting techniques and a heck of a lot of muscle memory to aid them. For the average woodworker with a pistol grip saw set, it comes down to feel. Most set has a pitch guideline on them that you can adjust to match the saw. The finer the pitch, the smaller the set. My recommendation is to set this adjustment to a pitch that is finer than the actual pitch of the saw you are working on. Sometimes several times finer in fact. set can be added and set can be removed but I find it easier to add more than take it away. Often times the setting process is helpful in adjusting a saw that isn’t running true too so the best thing is to skew to the finer set and then make several test cuts altering the set to get the right feel. With each test cut make sure you saw enough to let friction heat up the saw plate causing it to expand. You may think you have it right only to find the saw plate expands in the middle of a cut and starts to bind.

I find that once I have a saw set, I don’t need to reset it until I have sharpened the saw at least once more. In other words, every 3rd sharpening is a good rule of thumb. So while set is a little more touchy feely than rake and fleam, remember that it is also part of the geometry that effect how the saw cuts. Don neglect to alter the set in order to tune a saw. I have certainly been guilty of just relying on rake and fleam to solve all my problems. Though if I’m being honest usually the adjustments I make in set entail reducing the amount rather than increasing it.

Hopefully this treatise will help you wrap your head around these concepts. Don’t over analyze it but rather relish in our ability to be able to finely tune our hand saws. For the average hobbyist, pitch a number in the middle of the above ranges and you will do just fine. If you are more adventurous and looking for that “perfect” saw, consider each and every task as an equation to be solved with a little creative tooth geometry. Is it any wonder why masters of the saw like Ron Herman have so many saws? Once you solve one of these geometry equations you will find yourself getting more saws and tuning them to specific tasks. Careful this is a slippery slope and soon you will be talking about witchcraft like sloping gullets and progressive rake and fleam.